“Back of the Book” Answers

by Richard White

2012-10-04

Welcome back to the new school year!

One of the very first things I did when I started incorporating technology into my teaching was to put homework answers online for my physics students. I was relatively new to teaching physics, and what I learned pretty quickly was that my students, in attempting to solve a problem that could involve understanding how to apply multiple problem-solving steps in sequence, often found themselves getting stuck by one concept that they found especially challenging. Whether that one difficult concept occured at the beginning, the middle, or the end of the problem, they didn’t have the chance to work on anything else in the problem that occurred after that–they were stuck and couldn’t move on.

For simple problems, having access to the correct answer for an odd-numbered problem in the back of the book sometimes gave them enough of a clue that they could work their way backwards from that answer, and realize where they had made a mistake. But for more complex problems, they were dead in the water without a bit more in the way of hints on which direction they should proceed.

College textbook authors are aware of this problem, and most college-level chemistry and physics texts now offer some form of Student Solutions Manual that students can purchase (at considerable expense) for just such help. These student manuals usually cover some subset of all the problems in a textbook. Complete solutions manuals to these texts are also sometimes available, usually only to professors, and these are accompanied by dire warnings about the possible unintended consequences of sharing the contents with the young’uns.

This whole concept of gatekeeping information, or parsing it out to students on a “need to know” basis, runs completely counter to the idea of life-long learning, fostering self-guided discovery, and the current revolution in online learning.

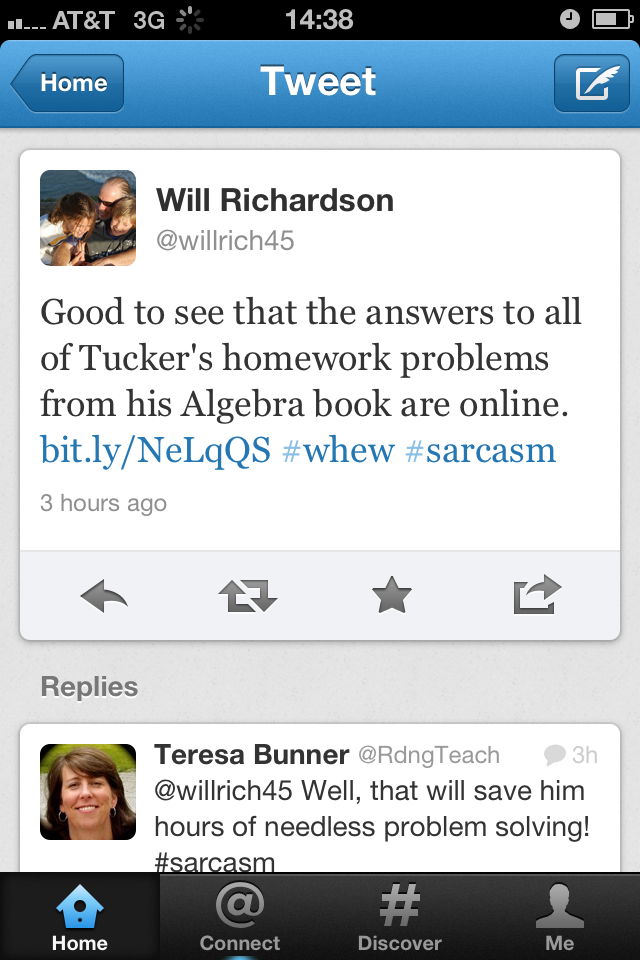

Will Richardson, an educational reformer, famously supported his daughter learning how to play a Journey song on the piano by following a tutorial on the Internet, even when her piano teacher objected, saying that she wasn’t advanced enough to learn the song. I applaud Will’s sensibilities on most things, but even he occasionally gets it wrong, as when he posted this tweet on September 6.

It *is* good to see all of Tucker’s homework answer posted online. This information regarding the question of whether or not he’s making the progress he needs to make is just-in-time feedback that Tucker can use to step over the stumbling blocks that would otherwise require that he try to ask the question during class, or go to school early to talk to the teacher, or stay late after school. Why make him wait? Why hold his progress in completing homework hostage?

The obvious concern is that many students–perhaps even good students–may fall into the habit of taking the easy way out. If the solutions are posted, then students may be tempted to simply copy them, which is a double whammy against him or her: not only are they getting credit for work that they haven’t done (and getting reinforcement for cheating in the process), they’ve managed to temporarily avoid acquiring the very skills that those homework problems were meant to foster.

These are the perils of always-on access to information, and I’m afraid the obvious benefits come with some risks, and managing those risks becomes part of what we need to teach our children.

Perhaps part of teaching children to be lifelong learners is teaching them not only WHAT to learn–readin’, writin’, ‘rithmetic, social skills, expository writing, critical thinking, etc.–but HOW to learn. That necessarily requires presenting them with content, and with strategies on how to access that content and use it best to their advantage.

It will be up to Will (and his son Tucker) to find a way to best manage learning in the new world, and that process will almost certainly involve a few potholes along the road. In the meantime, however, Mr. Richardson is far brighter and forward thinking than this one errant tweet might lead one to believe. I encourage you to read his blog.

Bringing things back around to my own classroom, my AP Physics classes are using a new text this year, and those homework problems aren’t easy. A significant part of my prep time for class is now devoted to writing up solutions to the homework problems that I’ve assigned, and making those available to my students online where they have access to them. The reality of the situation is that I’m going to have to go over those problems with them at some point, perhaps writing out the solutions in class (wasting additional face time with them, after they’ve wasted time struggling with the problems at home), or writing the solutions out in advance so that they can get the help they need when they need it, and not later.

It’s a good thing that I enjoy solving physics problems, because I’ve got a couple of hundred of them that I’m doing this year…!

Thanks for the pushback, and apologies for the “errant” Tweet. ;0)

My sarcasm was primarily directed at the textbook, not the availability of the answers. The problems he’s being required to answer are so irrelevant, uninteresting and divorced from reality that I don’t blame him at all for just wanting to get to the answer. That’s pretty much all that counts. Frankly, I don’t care so much about the answer as I do the question and the process.

Hi, Will, and thanks for checking in. Pushback is all part of the conversation, isn’t it? and your gracious reply is much appreciated.

I keep hoping that the whole “textbook” problem will somehow just go away, although that’s just naive and wishful thinking on my part. Textbook-related issues such as bad content, too-frequent edition changes and price-gouging (my own students’ AP Physics textbook this year is a cool $270) have resulted in a mind-boggling array of responses from creative teachers. A physics colleague wrote his own texts (self-published, and being used by other teachers). A chemistry colleague is hard at work on his own iPad-based book using Apple’s iBooks Author. I’m putting up my entire computer science curriculum online (although my physics classes still need the infrastructure of that textbook). And the math department at my school–an independent K-12–years ago threw out the high school curriculum in favor of developing their own, which suits them very nicely, thank you.

Thanks again for the reply, and for your thought-provoking comments on Twitter and elsewhere.

Richard