Getting SaaSy: Software as a Service

====================================

2016-10-28

by Richard White

Ah, remember the glory years of installing software on a computer? Buying cardboard packages with floppy disks or CD-ROMs inside them, and spending an afternoon installing a new game or Microsoft Office on your desktop machine.

If you’re a bit younger, installing software got more convenient: later, you might gone to the Mac App Store, or iTunes, and downloaded software directly off the Internet.

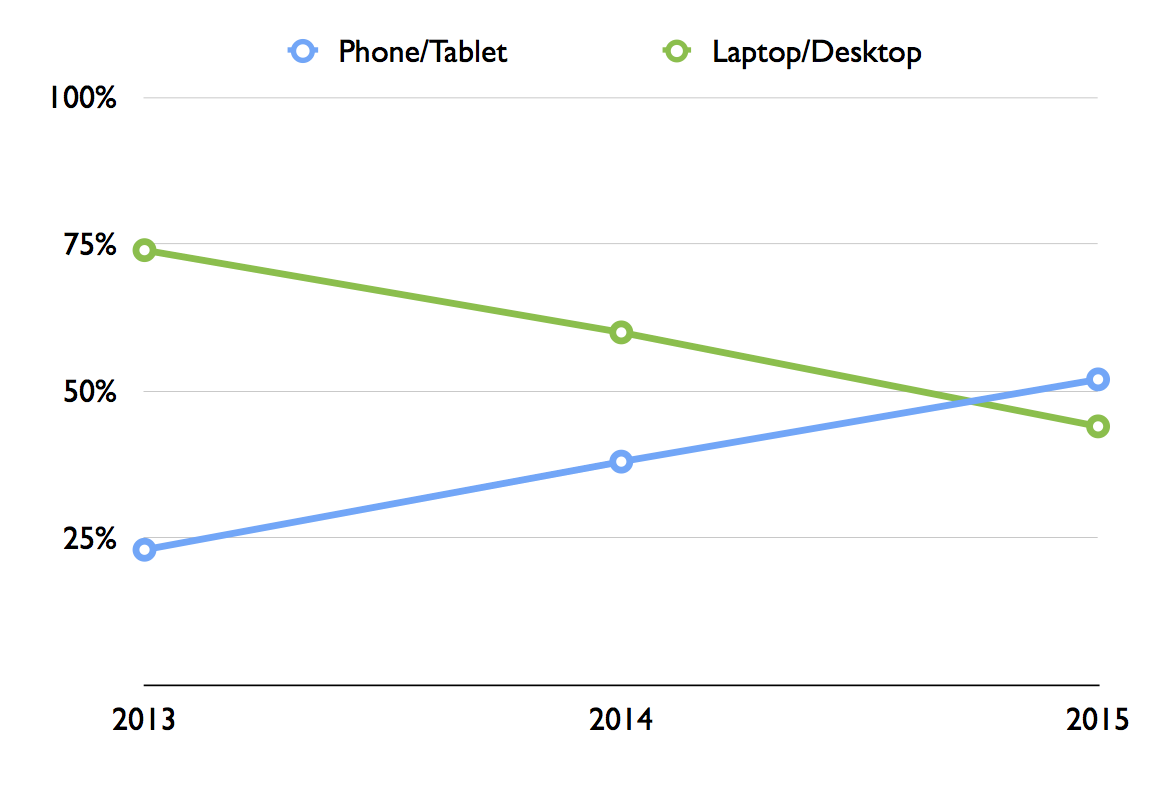

Even those halcyon days of software installation are on their way to becoming a memory, though, at least for some of us. That software you previously installed and ran on your computer is increasingly being replaced by “Software as a Service“, and if you aren’t familiar with “SaaS,” you almost certainly use it. SaaS provides you with the cloud-based equivalent of an installed program, often via an interface running in a web browser.

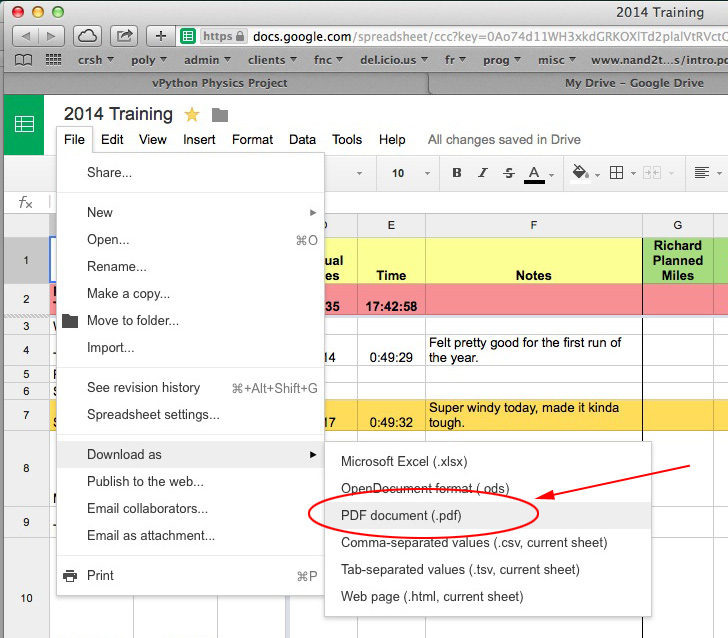

Google’s Docs, for example, provide you with the ability to create and edit word-processing or spreadsheet documents. When you use Google Docs, you’re not running the equivalent of Microsoft Word on your computer. Your browser is interacting with documents that have been made available to you over a network. Google is providing you with “Software as a Service.”

Google’s Docs are an example of a “free” service (in quotes because you do pay a price in terms of your privacy), but it’s more likely that a company will charge you for their SaaS. Spotify, for example, provides you with the ability to stream music onto your computer or mobile phone. There is a small app that you download to use their service, and it is this app that allows you to interact with their music delivery service in either free or paid form. The music doesn’t reside on your computer; the music is streamed to your computer as a service.

I’m a bit old school when it comes to these things, so I’m not that big a fan of SaaS. Sure, I’ve got a Netflix subscription, and I watch Game of Thrones via HBONow. But I don’t have 24×7 access to the Internet, and I don’t like the idea of my hardware having to lie dormant when I’m not connected.

This is a little more than just a philosophical debate. I’m a teacher, and as part of my job, I record and calculate students’ grades on assignments. I used to do this in a paper gradebook, and then quickly graduated to a spreadsheet system. Spreadsheets were practically made for teachers to record and calculate grades with. Some of my colleagues who weren’t so good with managing a spreadsheet bought specialized grade tracking software and installed it on their home computers. That works too.

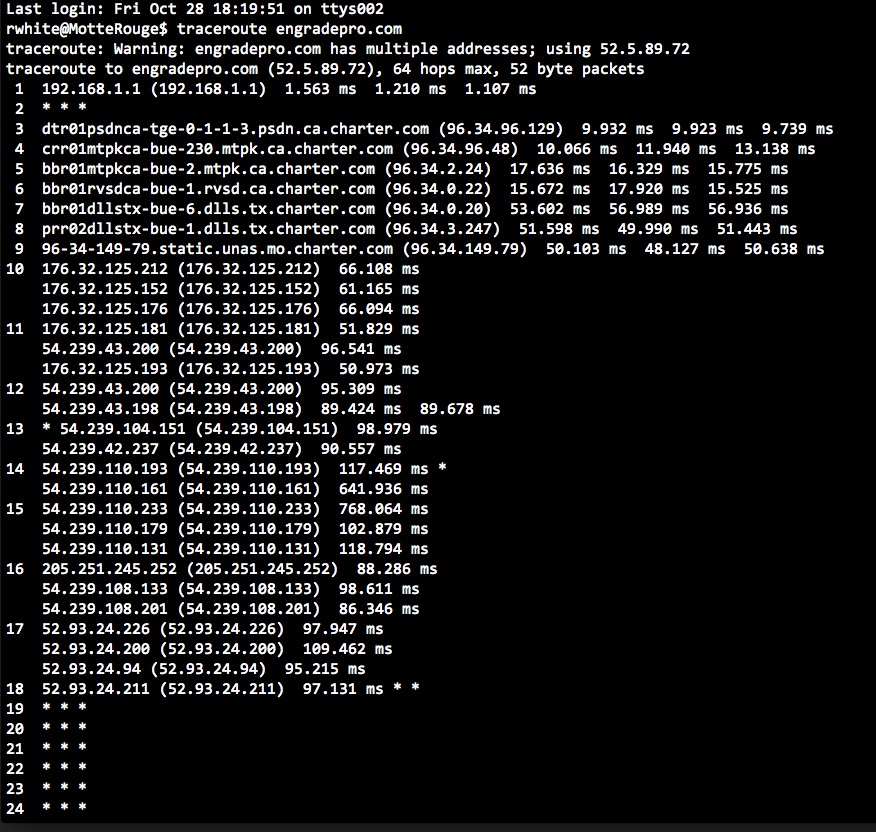

In the interest of providing students with ongoing access to their grades, I switched a few years ago to using a free service called Engrade, formerly at https://www.engrade.com. And with that move I entered the SaaS realm, using someone else’s software running in my browser, with access to my students’ grades via the Internet… assuming I have a connection. Which I usually do.

One of the downsides to SaaS is that you no longer have a copy of the software that is yours to use. When McGraw Hill purchased Engrade for $50 million, there was a new sheriff in town… and the service was no longer free.

And maybe that’s okay. Maybe McGraw Hill deserves to see some return on their investment in this company. Enough of my colleagues at my school site used Engrade that our school decided to pony up for a site license, so I’m still using Engrade. And that’s mostly good news…

…until their site goes down.

So, yeah. Software as a Service. Advantages and disadvantages. Pick your poison. Just be aware of the benefits and pitfalls of your options.

Next weekend I’ll be on a cross-country flight, writing up grades and comments for my students to be turned in the following week. I won’t have Internet. I won’t have Engrade. I won’t have Microsoft 360. I won’t have Spotify.

I’ll just have my laptop, with iTunes playing my old CDs that I ripped, and I’ll be writing comments in a text editor while consulting student grades in a spreadsheet, the way you do.

Like a Boss.